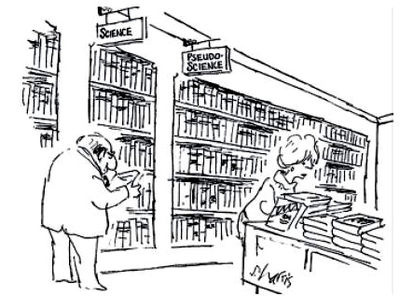

Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience are theories, beliefs and claims which are presented as scientific but do not adhere to the strict standards of science. They are usually not supported by evidence, not sufficiently tested or even implausible. Scientific terms are often misused or used in a confusing way to resemble real science. Pseudoscientific claims are often not falsifiable and expressed in unclear terms, with the intend to make them difficult to disprove.

The term "pseudoscience" has been in use since the 18th century and one of the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles". Current definitions are more or less based on the works of Thomas Huxley and Karl Popper. Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience[1][2]

Overview

There are several categories that distinguish science and pseudoscience. Basically, if a scientific claim does not meet scientific norms it can be classified as pseudoscience. To distinguish between bad or deceptive research in science and pseudoscience is often difficult. One difference is that pseudoscientific claims are often in conflict with current scientific knowledge and created specifically to support some model of thinking, while bad science tries to fit into the current model of science. Scientific jokes and fraud in science are not considered to be pesudoscience.

Pseudoscientists often use "experiments" to prove their claims, but manipulate the selection or the results to "show" that their claims are valid.[3] Often an "inverted Occam's Razor" comes to play: A complex and/or absurd theorie is preferred to a simple explanation. Also, pseudoscience never changes and updates its views when new evidence is found. If it can be fitted into the theory, the evidence is embraced and used. If it does not fit, evidence is ignored, dismissed or claimed to be bogus.

Typical Characteristics

- Claims that are not supported by evidence. These claims often stand in conflict with current experimental data or to mathematical theories and sometimes even contradict common sense.

- Based on sources that cannot be validated

- Based on experiments that cannot be reproduced (or if, lead to different results)

- Contradicting Occam's Razor

- Systematically ignore evidence or only select fitting evidence

The seven sins of pseudoscience

Several science theoreticians have compiled lists of the sins that distinguish pseudoscience from real science. This includes lists by Langmuir ([1953] 1989), Gruenberger (1964), Dutch (1982), Bunge (1982), Radner and Radner (1982), Kitcher (1982, 30–54), Hansson (1983), Grove (1985), Thagard (1988), Glymour and Stalker (1990), Derkson (1993, 2001), Vollmer (1993), Ruse (1996, 300–306) and Mahner (2007)[4][5]. These are usually:

- Belief in authority: It is contended that some person or persons have a special ability to determine what is true or false. Others have to accept their judgments.

- Nonrepeatable experiments: Reliance is put on experiments that cannot be repeated by others with the same outcome.

- Handpicked examples: Handpicked examples are used although they are not representative of the general category that the investigation refers to.

- Unwillingness to test: A theory is not tested although it is possible to test it.

- Disregard of refuting information: Observations or experiments that conflict with a theory are neglected.

- Built-in subterfuge: The testing of a theory is so arranged that the theory can only be confirmed, never disconfirmed, by the outcome.

- Explanations are abandoned without replacement. Tenable explanations are given up without being replaced, so that the new theory leaves much more unexplained than the previous one. (Hansson 1983)

Quotese

- In science, the burden of proof falls upon the claimant; and the more extraordinary a claim, the heavier is the burden of proof demanded. The true skeptic takes an agnostic position, one that says the claim is not proved rather than disproved. He asserts that the claimant has not borne the burden of proof and that science must continue to build its cognitive map of reality without incorporating the extraordinary claim as a new "fact." Since the true skeptic does not assert a claim, he has no burden to prove anything. He just goes on using the established theories of "conventional science" as usual. But if a critic asserts that there is evidence for disproof, that he has a negative hypothesis --saying, for instance, that a seeming psi result was actually due to an artifact--he is making a claim and therefore also has to bear a burden of proof [...][6]

Literature

- ↑ T. H. Huxley: Science and Pseudo-Science

- ↑ „Incidentally, the philosopher Karl Popper coined the term, ‘pseudo-science’. The examples he gave were (Western) astrology and homeopathy, the medical system developed in Germany.“ V. V. S. Sarma: Natural calamities and pseudoscientific menace. Current Science 90:2 (25. Januar 2006); „The notion of pseudoscience, as coined by philosopher Karl Popper is discussed in the context of its application to library science and its implications for selection.“ Graham Howard: Pseudo Science and Selection. Collection Management 29:2 (24. Mai 2005)

- ↑ http://www.xy44.de/belladonna/ Gerhard Bruhn, Erhard Wielandt, Klaus Keck: Pseudowissenschaften an der Universität Leipzig

- ↑ Science and Pseudo-Science, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Deerksen A.A: The seven sins of pseudo-science, Journal for General Philosophy of Science, Volume 24, Number 1 / März 1993

- ↑ Marcello Truzzi, On Pseudo-Skepticism